Why January 1st?

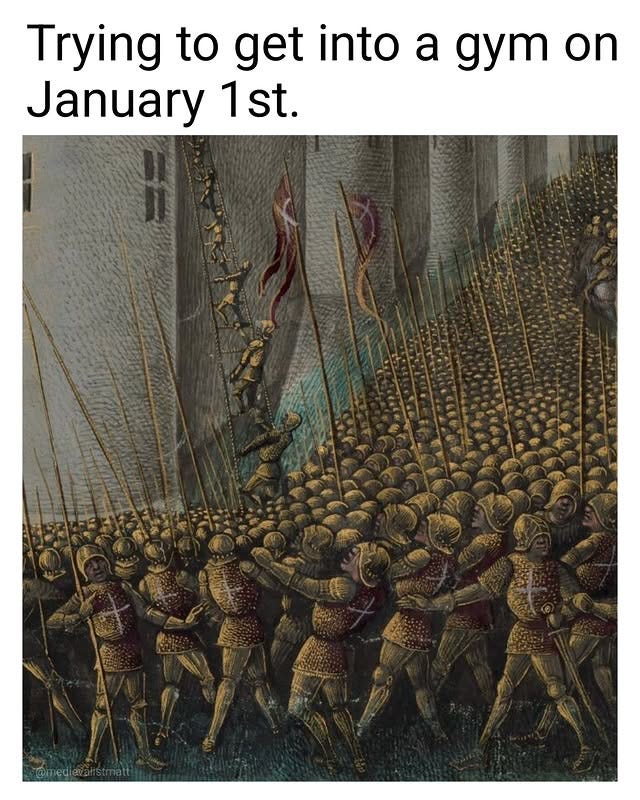

It’s a question that seems to make the rounds every year: What sense does it make to start a new calendar year on this date? When the weather in the Northern Hemisphere, in which our calendar was born, is cold and lacking sunlight? A staid bookend to our revelries, of whichever faith or cultural traditions we maintain through December? The sudden turn toward asceticism seems misplaced; a strict insistence on dieting and exercise, self-discipline and lofty goals, in radical opposition to the feasting and leisure of the holiday season through which we have just passed. It presumes a preceding period of gluttony and extravagance, of sloth and hedonism, that must be taken to task by an imposition of Spartan habits, a sharp return to minimalism, and the resultant birth of a new self. Yet it’s not a new question of our age, borne of our desire to hibernate on the couch, forgoing exercise.

Our placement of the new year at January 1st is from the Roman Empire, but in the northern lands conquered by Rome, the common people continued to mark the new year at either the Winter Solstice/Yule/Christmas or the Spring Equinox, with some agrarian communities still reckoning the new year at the harvest in September. A sermon by the Anglo-Saxon abbot Ælfric of Eynsham (c. 955–c. 1025) bemoans the naming of January 1st as “Year’s Day,” since it lacked spiritual significance. For him, its basis in custom wasn’t a good enough reason. I think many of us nowadays would agree with him on that point. I tend to think the Spring Equinox makes more sense as New Year’s Day, which puts me in good company with the early Medievals, who recognized March 21st as the anniversary of the birth of time itself, of the day on which the sun and moon first appeared. In fact, from the late Medieval period until 1752, England recognized March 25 as the start of each new year.1

Here we go a-wassailing

Regardless of which date was fixed as New Year’s, agricultural field work often began in January, with an assessment of the land and winter ploughing. Plough Monday followed January 6, Epiphany (the feast of the 3 Kings or Magi who visited the infant Jesus), also known as Twelfth Night for it’s position marking the end of the 12 days of Christmas. Twelfth Night was often the wildest party of the season, after which the laborers returned to their regular work (although they still marked the Christmas season until Candlemas on February 2). Plough Monday appears to have been celebrated from the 15th century until the Reformation, though it persisted after that in the form of a monetary collection by farm laborers for maintenance of agricultural tools. It involved blessings of fields and ploughs, and a last grand feast for the working people.2 In that respect, perhaps our leap from the celebrations of December to the austere resolutions of January are not so very different.

Plough Monday customs appear to be remnants of a more ancient ritual, likely a Christianized Pagan tradition, named in an 11th century manuscript as the Æcerbot (“field remedy”). The rituals were complex and took all day to complete. One of the exhortations to the earth was the Old English Wes þu hál or Be hale/ Be thou well. A century later, the phrase was used in toasting someone’s health, typically with ale or warm spiced wine, and from there was shortened to Wassail. By the 16th century, people were wassailing their orchards, offering cider and bread to the dormant winter trees, with songs and requests for good fruit that year. The carol Here we come a-wassailing was not written until the mid-19th century, though it referred back to older customs of door-to-door holiday merry-making.3

The history of wassailing is more murky than I knew, however. The linear leap from field blessing to communal drink to orchard rite to synonym for rowdy caroling is not supported by primary sources. Food historian and author Brigitte Webster, in a Zoom call hosted by Hearthstone Fables (please go and subscribe), noted that the first written reference to orchard wassailing was an Elizabethan era court document, which lodged a complaint of unruly boys in the plaintiff’s apple orchard. We also learned from her that the traditional meat served at Twelfth Night changed over the years from venison to turkey, when that bird from the Americas became a common import via Spain. Apparently they never really liked the taste of peacock anyway.4 Turkey has been our family’s go-to for January feasting, but only because it goes on sale after Christmas.

Sugar and Spices and Sweets, Oh My!

Which brings us to the history of holiday sweets. The oldest-known treats in northern lands for the winter solstice, and thence for Christmas, were crunchy spiced biscuits from Persia, brought by way of 8th century spice routes. These biscuits kept well in the cold, which meant that hosts needn’t serve stale food to guests over the long Yuletide/ Christmas season. The 1st true “Christmas cookie” is claimed by the bakers’ guild in Nuremberg, Germany: Lebkuchen, developed in the 13th century using spices from the East. From this proceeded other iterations of gingerbread. Dutch settlers brought koeptje to the New World, along with the tradition of leaving these cookies for St. Nicholas. Icing evolved from a thin glaze in the 17th century to thick piping in the 20th. Cookie cutters, like so many other Christmas trappings, came to the U.S. from Germany in the late Victorian period.5 I don’t think there’s been a Christmas when we didn’t have homemade lebkuchen in my family, but I had no idea its history was so illustrious; a cookie birthed at a crossroad of medieval spice routes.

Candy canes likely started in 1670, as sugar sticks bent like a shepherd’s crook, to keep the children quiet during holiday church services. They were solid white until 1900, when someone in the U.S. added the red stripes. Their manufacture became mechanized in 1921, and peppermint did not become the main flavor until 1950.6

The history of sugar plums, and one man’s struggle to make them at home, is worth a watch here, or at least bookmarking for next December:

Photos from our Christmastide

The plan to get our bees through winter is multifaceted, and some aspects are based in folklore. So we’ve made sure to wish them well on holidays; holly sprigs at Christmas and chalked hives for Epiphany, and of course I talk to them. The chalk blessing is the same we use to bless the doorframes of the house: 20+C+M+B+25, which initials represent the apocryphal names of the Magi (Caspar, Melchior, Balthazar) as well as Christus mansionem benedicat (may Christ bless the house).

Happy New Year!

I hope you had a pleasant holiday season, and that 2025 brings you good times and plenty! What is your favorite holiday dessert? Do you make New Year’s resolutions? If you could pick a different date for the new year, when would it be? Have you been harvesting anything, or just gazing dreamy-eyed at seed catalogues? In any case, Be thou well!

—Erin, in Michigan

Winters in the World: A Journey Through the Anglo-Saxon Year, by Eleanor Parker, 2022

Ibid; purchases through affiliate links support our work here at no additional cost to you.

Ibid

Brigitte Webster, Zoom presentation January 4, 2025, including information from her book Eating with the Tudors: Food and Recipes (2023). Thanks to host

You chalked your beehive!! That makes my heart so happy.

I resonate so deeply with everything here, and though I'm pausing my deep-dive into Plough Monday till next winter, I'm so enamored of it.

The varying new year days that crop up in calendars are fascinating. The categorical thinker in me used to get all out-of-sorts trying to reconcile all those different "first days," but I've grown to love the variation. All Saints' feels like a new year to me since I arrived on the farm back in the day, and after learning about the poignant intersections of time-reckoning in the Annunciation - and, since falling head over heels for the arrival of spring after gray PNW winters - that feels like somewhat of a new year, too. In our stage of life, with kiddos in school, the beginning of September also feels like a new year (shoutout to our Orthodox friends here, who start a new liturgical year then!)

It was so awesome getting to spend time chatting about Twelfth Night with you, Brigitte, & everyone else! And I also thought that anecdote was AMAZING about our first written evidence of an orchard wassail being a formal complain!

I loved this—a wonderful post-Christmas pick-me-up! Even though I like to extend the holiday season through the 12 Days of Christmas, it’s still not long enough, lol.

That being the case, I’m never ready for January 1, and the fresh start and intentions for the new year, blah, blah, blah. I just want to cocoon in holiday mode a little longer!

Garden pics are wonderful, as usual! Especially your festive hives! 🌲 (“Make Christianity weird again”? Sounds very intriguing!) Today, I harvested the last of the parsnips—now I’m off to peel and roast a few for dinner!

Fave holiday cookie: shortbread by a mile! How about you?